The photo taken in 1963 shows He Xiangning jointly creating a painting with prominent artists Fu Baoshi (left) and Pan Tianshou (center). CHINA DAILY

A girl named He Xiangning was born to an affluent family in Hong Kong in 1878.

Her parents had no expectation that she, their ninth child, would become an accomplished person. They only wanted her to be obedient and quiet, like other women were expected to be during China's feudal era.

Decades later, He rose to fame as a revolutionary, social activist and avid advocate of women's rights. She served in a number of high-ranking governmental positions after the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, and today she is recognized as one of the nation's greatest women of the 20th century.

He's achievements as a gifted and well-trained painter, however, are less well-known to the public.

The New Paintings of Flowing Water and High Mountains, an exhibition at the Art Museum of Beijing Fine Art Academy running through Feb 28, reveals her diverse craftsmanship and extensive connections in cultural circles.

The exhibition showcases He's paintings and works she collaborated on from the collection of the He Xiangning Art Museum in Shenzhen, Guangdong province. The institution, which opened in 1997, is dedicated to the research and display of He's work.

Also on display are paintings offered by the academy that were created by noted artists whom He got on well after she relocated to Beijing in 1949. She resided in the capital until her death in 1972.

The exhibition offers a distinctive perspective into the extraordinary life of a woman whose commitment to the progress of modern China complemented her artistic evolution over the course of more than seven decades, says Xue Liang, a senior curator of the academy's museum.

The Beijing exhibition features works by He Xiangning, including Chrysanthemums. CHINA DAILY

A girl of ideals

The works being exhibited date back as early as the 1910s, during which He depicted ferocious animals, such as tigers and lions, and plants that symbolize integrity in the Chinese cultural tradition, such as plums and chrysanthemums.

He's paintings convey a courageous, heroic spirit rather than the gentle, lovely feminine temperament that can be found in many works painted by women in Chinese art history.

During her girlhood, He showed intelligence, distinctive determination and a fighting spirit.

He's father, He Zai, a successful business owner and a follower of feudal thoughts, established sishu, a traditional home-schooling structure popular among well-off families more than 100 years ago. But he excluded his daughters from attending it, for he believed women were inferior to men and need not learn.

He Xiangning, who received a considerable allowance from her parents, had little interest in luxury spending. Instead, she saved the money to buy books that were used at the home school. When she had questions, she turned to her brothers for help or asked servants to seek answers from the sishu tutors behind her father's back.

Self-learning planted the seeds of He's independence and gave her the will to stand up against the oppression of women.

He was strongly opposed to foot binding, a practice in feudal China in which young girls were forced to have their feet bound so as to stop them from growing. It was a popular practice because a woman's small feet were considered a symbol of beauty and of a higher social standing.

She defied her parents, who insisted on binding her feet. Each time they did it, she would use a pair of scissors, which she had hid in the family altar, to cut the tight bandages. She was so insistent that her parents finally gave up the practice.

As He grew up, her family worried that her normal-sized feet, which were considered big and not good looking at the time, would frighten away possible suitors.

But at age 19, He married Liao Zhongkai, an American-born Chinese from the United States studying in Hong Kong who aspired for social transformation and who had said he wanted to wed a woman who was free of foot binding.

In 1902, He sold her dowry items, including jewelry and furniture, to raise money for her and her husband to study in Japan.

After arriving there, the couple met revolutionaries including Sun Yatsen and were inspired by their ideas to end feudalism in China. The couple were among the earliest members of the Tongmenghui (China Revolutionary Alliance), an antimonarchist society Sun founded in Tokyo in 1905 which became a predecessor of the Kuomintang.

The Beijing exhibition features works by He Xiangning, including Plum. CHINA DAILY

Revolutionary path

While Liao studied political and economic sciences at university in Japan, He attended women's schools to study natural sciences and fine arts. She achieved excellence in classical ink painting, a tradition in both China and Japan. She was especially adept at portraying natural landscapes, flowers and animals.

He's paintings present an accumulation of Chinese cultural traditions and a scholarly temperament. They also express her desire for social reform and her devotion to raising the profile of women.

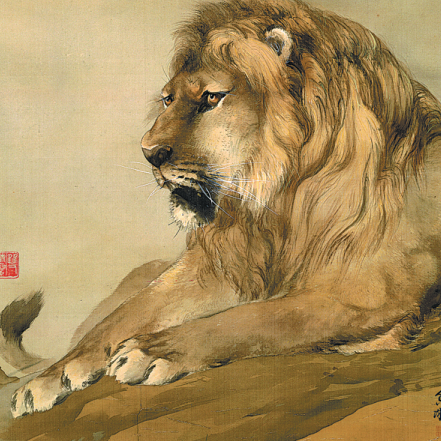

Lion, an iconic work in He's oeuvre in which she painted on silk in 1914, has been exhibited widely and is part of the current display at the Beijing Fine Art Academy's museum.

Yu Feng, a painter and essayist, said He created "smooth, delicate drawings of the beast's loose hairs, its bone structure and muscles, giving the work a lifelike, three-dimensional feel".

"She presented the imposing manner of lions and tigers to symbolize the awakening awareness of a nation," Yu said.

In addition, pine trees, bamboo, plums and chrysanthemums were recurring objects both in the works He made on her own and in landscapes she collaborated on.

Paintings she produced in the 1910s and the early 1920s are highly decorative, featuring vibrant colors, meticulous brushwork and full-bodied composition.

After Liao was murdered in 1925, He's paintings gradually took on a calm, reserved style.

The Beijing exhibition features works by He Xiangning, including her iconic work, Lion. CHINA DAILY

Yu said He then began to adopt a reduced color palette and sought to showcase varied presentations by layering shades of ink.

Yu said the change in He's works displayed simplicity and were indicative of a manner unique to the tradition of classical Chinese literati paintings; her brushwork expressed her anger over the setbacks in the revolutionary cause and the concerns she had about her country.

He's vivid palette returned in the 1950s and '60s to reflect her joy at a booming scene of socialist constructions across China.

Yi E, a senior researcher at the National Art Museum of China in Beijing, says He's collaboration with established painters, including those working at the Beijing Fine Art Academy, reached its peak in the 1950s. And when she traveled south to Shanghai, Nanjing in Jiangsu province or Hangzhou, capital of Zhejiang province, to escape the winters in North China, she would co-create paintings with artists there, including Huang Binhong, Pan Tianshou and Fu Baoshi, which brought her great delight.

He was elected chairperson of the China Artists Association in 1960.Her passion for painting lasted until late in her life.

"It (painting) won't tire me," He once said to her family. "I've been painting all my life. I feel happiest right now."

Yu said every time she visited He Xiangning, she would show paintings she coproduced with prominent artists.

"There were always half-done paintings on her desk which depicted a pine tree, a stone or a plum branch," Yu said.

"She said, 'I'm too weak to finish (the paintings). I will be happy if other painters could complete them for me.'"

Contact the writer at linqi@chinadaily.com.cn

If you have any problems with this article, please contact us at app@chinadaily.com.cn and we'll immediately get back to you.